Dream Factory - GMH design at Fishermans bend 1964 - 2020 Exhibition now closed

From Aussie classics to contemporary concept cars, this exhibition captures the unfinished story of design and innovation at General Motors Holden (GMH) Fishermans Bend, home to Melbourne’s most successful city-based automotive factory- focusing on the Technical Centre, which opened in 1964.

The GMH Technical Centre: a place for design

In June 1964, General Motors Holden (GMH) opened the Technical Centre at its Fishermans Bend site in Melbourne, Victoria, the company’s headquarters since 1936. An extension to GMH engineering’s Plant Nº. 3, the centre was designed by Stephenson & Turner, an architectural firm renowned across the region for its interwar and wartime hospital designs. It is less known for its contemporary Ford manufacturing and assembly plant in Homebush, New South Wales, designed in 1936. Indeed, Stephenson & Turner’s contribution, like that of Australian architects in general, to the architecture of manufacturing in this country is a story yet to be told. As Philip Goad has recently argued:

In Australian twentieth century architectural histories, the trajectory of modernism has been a key focus as has the documentation of residential architecture as a banner of progressive design ideas ... But a foundational icon of modernism in architecture – the factory – and the trope of the so-called ‘factory’ aesthetic intrinsic to modernism’s rise and its Australian appearance has been – remarkably – little studied.

Australia’s booming postwar manufacturing sector demanded new plants, specialised facilities and head offices, and Stephenson & Turner was commissioned to design GMH’s new manufacturing and research facility on Princes Highway, Dandenong, which opened in 1956. The smaller Technical Centre came a few years later, and both buildings were conceived in Stephenson & Turner’s well-tuned idiom of rationalist modernism.

While the centre was not a factory – being a specialised facility for the design and engineering of industrial products – it belongs in the category of industrial architecture discussed by Goad. The folio of drawings prepared by the architects for the three-storey building shows a sequence of carefully designed spaces, from the external courtyard with an abstract modernist fountain through to the more private but still accessible spaces of auditorium, dining rooms, conference room and so on.

The centre is a modest work for the firm, scarcely known outside the world of GMH. Yet for nearly 60 years it was the powerhouse of one of the most successful industrial design studios in Australia. Its significance thus is twofold: an architectural object representing a manufacturing sector that underwrote Australian postwar prosperity and the home of the GMH design studio.

In June 1964, General Motors Holden (GMH) opened the Technical Centre at its Fishermans Bend site in Melbourne, Victoria, the company’s headquarters since 1936. An extension to GMH engineering’s Plant Nº. 3, the centre was designed by Stephenson & Turner, an architectural firm renowned across the region for its interwar and wartime hospital designs. It is less known for its contemporary Ford manufacturing and assembly plant in Homebush, New South Wales, designed in 1936. Indeed, Stephenson & Turner’s contribution, like that of Australian architects in general, to the architecture of manufacturing in this country is a story yet to be told. As Philip Goad has recently argued:

In Australian twentieth century architectural histories, the trajectory of modernism has been a key focus as has the documentation of residential architecture as a banner of progressive design ideas ... But a foundational icon of modernism in architecture – the factory – and the trope of the so-called ‘factory’ aesthetic intrinsic to modernism’s rise and its Australian appearance has been – remarkably – little studied.

Australia’s booming postwar manufacturing sector demanded new plants, specialised facilities and head offices, and Stephenson & Turner was commissioned to design GMH’s new manufacturing and research facility on Princes Highway, Dandenong, which opened in 1956. The smaller Technical Centre came a few years later, and both buildings were conceived in Stephenson & Turner’s well-tuned idiom of rationalist modernism.

While the centre was not a factory – being a specialised facility for the design and engineering of industrial products – it belongs in the category of industrial architecture discussed by Goad. The folio of drawings prepared by the architects for the three-storey building shows a sequence of carefully designed spaces, from the external courtyard with an abstract modernist fountain through to the more private but still accessible spaces of auditorium, dining rooms, conference room and so on.

The centre is a modest work for the firm, scarcely known outside the world of GMH. Yet for nearly 60 years it was the powerhouse of one of the most successful industrial design studios in Australia. Its significance thus is twofold: an architectural object representing a manufacturing sector that underwrote Australian postwar prosperity and the home of the GMH design studio.

The design studio

The launch of the Technical Centre in June 1964 was arranged by General Motors (GM) to coincide with the opening of its Opel Technical Centre, in Rüsselsheim am Main, Germany. GMH at Fishermans Bend and Opel were the offspring of GM’s technical centre at Warren, Michigan, designed by Eero Saarinen a decade before. For the first time, the design ambition of GM, the world’s largest auto manufacturer and one of its largest corporations for much of the 20th century, was embodied in its architecture – not in one building but in the spectacular campus of more than 20 buildings. The Opel design studio was, at its opening, ‘the largest design studio owned by an automaker in Europe’, and, like at Fishermans Bend on that June day, the public was allowed to visit the building and freely walk among its exhibits. The studios were then forever sealed off from prying eyes.

The ambition of the enterprise and the excitement of the occasion were captured in Peter Nankervis’s futuristic murals painted on the walls of the design studio for the opening, projecting an imagined ‘autopia’. Like its German counterpart, the Melbourne facility mirrored, on a small scale, the work of its parent company, grounding the design staff in the skills and competencies that allowed them to participate as partners in the GM global behemoth. It co-located its design and engineering facilities and departments, which had been housed elsewhere, with the administration and workshop, auditorium, executive dining room, viewing courtyard and archive.

The brochure published to celebrate the opening of the facility illustrated the ‘Technical Centre in Action’. It described in some detail the activities of each department: Styling (‘stylists create the shape. Engineers design the structure’); Production Design Drawing Office (‘accuracy in detail’); Rig Test Laboratory (‘the destroyers’); Central Laboratory (‘the analysts’); and GMH Proving Ground (‘tested around the clock’). The brochure concluded with an organisational chart listing the activities under each department. Those under Styling included sketches and comparative data, scale outlines and small models, seating buck, clay model, fibreglass model, trim and colour detail. Sometimes these diverse activities, which took place in different studios, were arranged together in one studio for a photo shoot, a sort of précis of the work the studios carried out in combination.

The Technical Centre was refurbished over the years, and when a new headquarters opened next door in 2004 the design department remained, expanding to occupy all of the first and second levels and some of the ground level. Things remained in this way until the end in 2020.

General Motors was, in 1964, a highly coordinated global operation, with advanced studios in Detroit and at the Vauxhall, Opel and Holden plants. Under the expansionist Alfred P. Sloan, GM had bought Vauxhall of England in 1925, an 80 per cent stake in the German Opel enterprise in 1929, which increased to full ownership two years later, and, during the Depression, Holden in 1931. As Bradford Wernie noted in 2008, GM was cost-conscious and ‘decided to build its business mostly by buying established companies rather than building them from scratch, particularly the three that have kept their brand identities: Holden, Opel and Vauxhall’. Elaborating, Wernie argued:

Working according to the credo of empire builder Alfred Sloan, GM kept a hands-off policy when it came to the cultures and operations of its foreign subsidiaries, albeit with a touch of Detroit paternalism. Few American consumers would know that the Saturn Astra started life in Germany as an Opel Astra or that the Pontiac G8 originated in Australia as a Holden Commodore. The Vauxhall brand is still sold only in Great Britain, even though its vehicles now are just rebadged Opels.

The launch of the Technical Centre in June 1964 was arranged by General Motors (GM) to coincide with the opening of its Opel Technical Centre, in Rüsselsheim am Main, Germany. GMH at Fishermans Bend and Opel were the offspring of GM’s technical centre at Warren, Michigan, designed by Eero Saarinen a decade before. For the first time, the design ambition of GM, the world’s largest auto manufacturer and one of its largest corporations for much of the 20th century, was embodied in its architecture – not in one building but in the spectacular campus of more than 20 buildings. The Opel design studio was, at its opening, ‘the largest design studio owned by an automaker in Europe’, and, like at Fishermans Bend on that June day, the public was allowed to visit the building and freely walk among its exhibits. The studios were then forever sealed off from prying eyes.

The ambition of the enterprise and the excitement of the occasion were captured in Peter Nankervis’s futuristic murals painted on the walls of the design studio for the opening, projecting an imagined ‘autopia’. Like its German counterpart, the Melbourne facility mirrored, on a small scale, the work of its parent company, grounding the design staff in the skills and competencies that allowed them to participate as partners in the GM global behemoth. It co-located its design and engineering facilities and departments, which had been housed elsewhere, with the administration and workshop, auditorium, executive dining room, viewing courtyard and archive.

The brochure published to celebrate the opening of the facility illustrated the ‘Technical Centre in Action’. It described in some detail the activities of each department: Styling (‘stylists create the shape. Engineers design the structure’); Production Design Drawing Office (‘accuracy in detail’); Rig Test Laboratory (‘the destroyers’); Central Laboratory (‘the analysts’); and GMH Proving Ground (‘tested around the clock’). The brochure concluded with an organisational chart listing the activities under each department. Those under Styling included sketches and comparative data, scale outlines and small models, seating buck, clay model, fibreglass model, trim and colour detail. Sometimes these diverse activities, which took place in different studios, were arranged together in one studio for a photo shoot, a sort of précis of the work the studios carried out in combination.

The Technical Centre was refurbished over the years, and when a new headquarters opened next door in 2004 the design department remained, expanding to occupy all of the first and second levels and some of the ground level. Things remained in this way until the end in 2020.

General Motors was, in 1964, a highly coordinated global operation, with advanced studios in Detroit and at the Vauxhall, Opel and Holden plants. Under the expansionist Alfred P. Sloan, GM had bought Vauxhall of England in 1925, an 80 per cent stake in the German Opel enterprise in 1929, which increased to full ownership two years later, and, during the Depression, Holden in 1931. As Bradford Wernie noted in 2008, GM was cost-conscious and ‘decided to build its business mostly by buying established companies rather than building them from scratch, particularly the three that have kept their brand identities: Holden, Opel and Vauxhall’. Elaborating, Wernie argued:

Working according to the credo of empire builder Alfred Sloan, GM kept a hands-off policy when it came to the cultures and operations of its foreign subsidiaries, albeit with a touch of Detroit paternalism. Few American consumers would know that the Saturn Astra started life in Germany as an Opel Astra or that the Pontiac G8 originated in Australia as a Holden Commodore. The Vauxhall brand is still sold only in Great Britain, even though its vehicles now are just rebadged Opels.

Staff circulated through the design studios, sharing expertise, skills and design ideas. During the war and in the immediate postwar years, senior Holden engineers and stylists had made the pilgrimage to Detroit when Harley Earl was the GM design director. There was a large contingent of GMH staff at Detroit during the development of the Holden 48–215 after the war, for example. Earl, a Sloan appointee, ‘relied on General Motors Overseas Operations’ (GMOO) executive Glen Smith to convey his design expectations to the various GM outposts beyond the USA.’

Thus, while Detroit dictated much in the way of Holden’s design ethos, it also left much up to the local Melbourne team. This remained the case until Bill Mitchell succeeded Earl in January 1959. Mitchell was an interventionist and, fuelled by America’s postwar prosperity and GM’s huge market dominance, held a global view. He took to visiting the outposts and kept an eye on things. The consequences for GMH were profound. In 1963, Mitchell chose Detroit-born GM designer Joe Schemansky to take up the newly created position of design director at Fishermans Bend, which he assumed a few months before the opening of the Technical Centre. While GMH had effective in-house designers and well-established drawings offices from the 1930s, as Norm Darwin has shown, the ‘design studio’ announced a new orientation towards design rather than drawing – concept rather than skill.

Schemansky had graduated from the Detroit Art Academy and, after working in a Detroit department store, joined GM’s styling department in 1937. He steadily worked his way up through the La Salle, Cadillac, Chevrolet and Pontiac studios from the late 1930s to the 1950s, and in 1961 was appointed chief designer for body-design coordination across the company. This appointment coincided with the design of the EJ Holden, overseen by Alfred Payze in Melbourne, which no-one at Detroit liked. Mitchell decided to oversee styling in Melbourne from Detroit until such time as GMH could improve, and it would be helped to do this by American designers on the team.

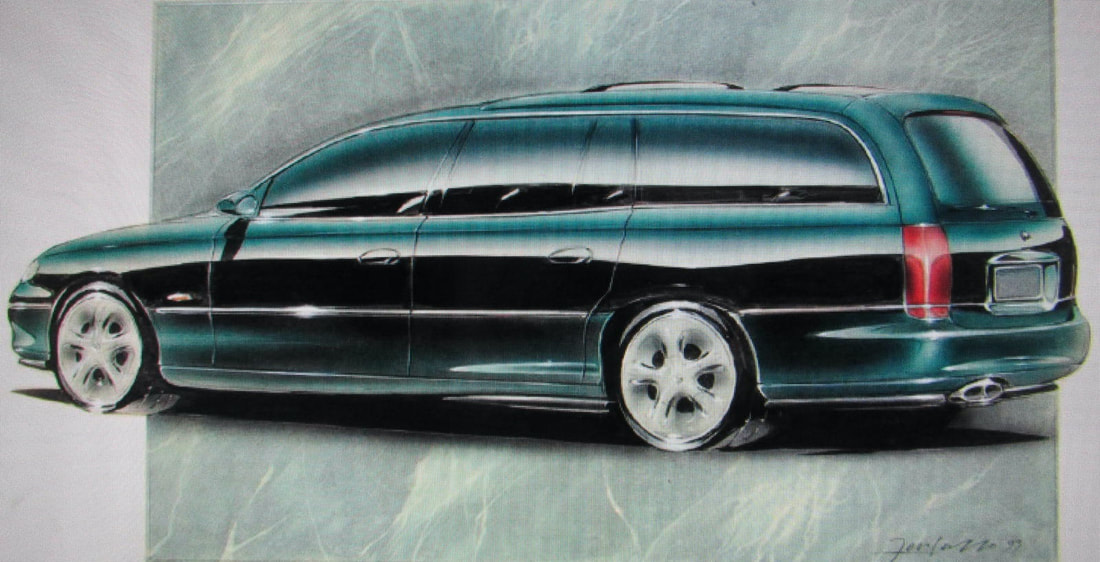

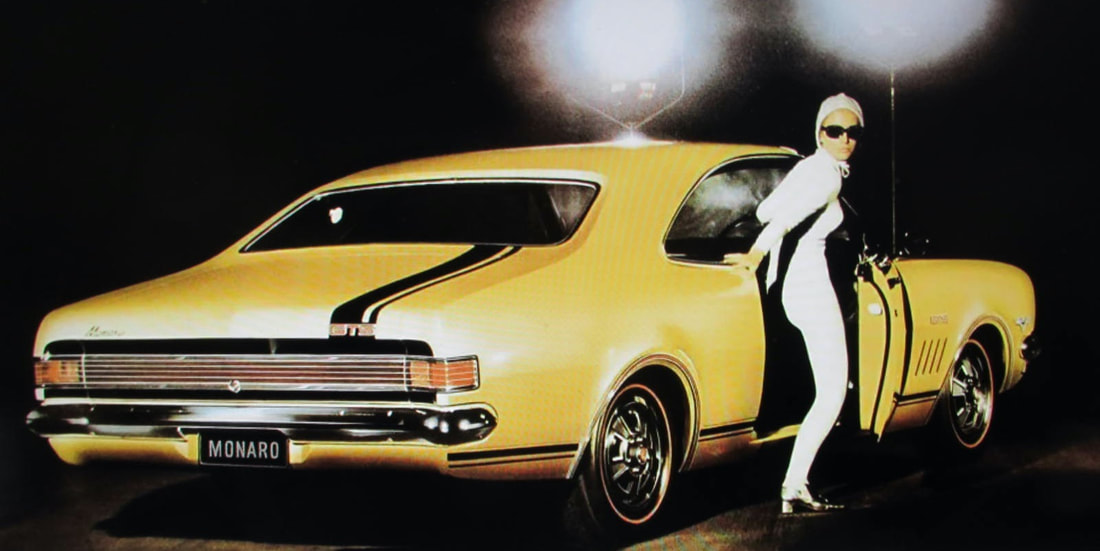

Under Schemansky the culture of design broadened. John Schinella, a graduate of New England School of Art, Boston, was sent to Fishermans Bend in 1965 for a six-month stint to help in the studio, but he stayed on as assistant design director for five years. With Schemansky’s oversight, Schinella led the team of long-serving designers, such as Payze, and young recruits, such as Peter Nankervis and Phillip Zmood; they designed the HK series, the first project produced by the new design team in the new facility. The HK Monaro was awarded Wheels magazine’s Car of the Year for 1968. With the LC and LJ Torana, the Monaro was taken to Bathurst, and in the ensuing gladiatorial Battles of the Mountain, against archrival Ford and others, these muscle cars transformed the image and market of GMH for the remainder of the century.

Schemansky brought to Melbourne new skills and design methods (such as the ‘tape drawing’) and recruited and fostered talented young Australian designers out of art and design schools. If they showed promise, Schemansky sent them into the GM corporation’s design studios in the United States, England and Germany; in later years, such work tours would include China and South Korea. Zmood recalls the impact of Detroit on him as a young designer in 1967:

The benefit of having the opportunity to work in 5 or 6 different design studios with designers varying in age and experience was challenging, it opened one’s mind to different design techniques and aesthetic solutions and assisted in improving your design talent.

Some studio chiefs would initiate a quick morning sketch session with the objective of each designer sketching as many different concept themes with a ball-point pen and 1 or 2 marker colours to highlight the graphics with flair. At the end of the morning all the respective designer’s work was mounted on large display boards for review with the design management that afternoon, some of the sketch concepts were selected for further exploration.

This created an extremely competitive environment, but you felt great if your sketch or sketches were selected. Further down the track your theme sometimes was passed on to the more experienced designers to develop in a clay model form. As all the GM brands were in the one design technical centre there was also competition between them.

Thus, while Detroit dictated much in the way of Holden’s design ethos, it also left much up to the local Melbourne team. This remained the case until Bill Mitchell succeeded Earl in January 1959. Mitchell was an interventionist and, fuelled by America’s postwar prosperity and GM’s huge market dominance, held a global view. He took to visiting the outposts and kept an eye on things. The consequences for GMH were profound. In 1963, Mitchell chose Detroit-born GM designer Joe Schemansky to take up the newly created position of design director at Fishermans Bend, which he assumed a few months before the opening of the Technical Centre. While GMH had effective in-house designers and well-established drawings offices from the 1930s, as Norm Darwin has shown, the ‘design studio’ announced a new orientation towards design rather than drawing – concept rather than skill.

Schemansky had graduated from the Detroit Art Academy and, after working in a Detroit department store, joined GM’s styling department in 1937. He steadily worked his way up through the La Salle, Cadillac, Chevrolet and Pontiac studios from the late 1930s to the 1950s, and in 1961 was appointed chief designer for body-design coordination across the company. This appointment coincided with the design of the EJ Holden, overseen by Alfred Payze in Melbourne, which no-one at Detroit liked. Mitchell decided to oversee styling in Melbourne from Detroit until such time as GMH could improve, and it would be helped to do this by American designers on the team.

Under Schemansky the culture of design broadened. John Schinella, a graduate of New England School of Art, Boston, was sent to Fishermans Bend in 1965 for a six-month stint to help in the studio, but he stayed on as assistant design director for five years. With Schemansky’s oversight, Schinella led the team of long-serving designers, such as Payze, and young recruits, such as Peter Nankervis and Phillip Zmood; they designed the HK series, the first project produced by the new design team in the new facility. The HK Monaro was awarded Wheels magazine’s Car of the Year for 1968. With the LC and LJ Torana, the Monaro was taken to Bathurst, and in the ensuing gladiatorial Battles of the Mountain, against archrival Ford and others, these muscle cars transformed the image and market of GMH for the remainder of the century.

Schemansky brought to Melbourne new skills and design methods (such as the ‘tape drawing’) and recruited and fostered talented young Australian designers out of art and design schools. If they showed promise, Schemansky sent them into the GM corporation’s design studios in the United States, England and Germany; in later years, such work tours would include China and South Korea. Zmood recalls the impact of Detroit on him as a young designer in 1967:

The benefit of having the opportunity to work in 5 or 6 different design studios with designers varying in age and experience was challenging, it opened one’s mind to different design techniques and aesthetic solutions and assisted in improving your design talent.

Some studio chiefs would initiate a quick morning sketch session with the objective of each designer sketching as many different concept themes with a ball-point pen and 1 or 2 marker colours to highlight the graphics with flair. At the end of the morning all the respective designer’s work was mounted on large display boards for review with the design management that afternoon, some of the sketch concepts were selected for further exploration.

This created an extremely competitive environment, but you felt great if your sketch or sketches were selected. Further down the track your theme sometimes was passed on to the more experienced designers to develop in a clay model form. As all the GM brands were in the one design technical centre there was also competition between them.

These tours of duty ensured that the GM DNA was distributed among its studios, but it did not obliterate the local design initiative. For a relatively small operation by GM standards, GMH held up its part of the bargain, designing not only for the Australian market but also for an export market. Schemansky retired from GMH in 1975 and was replaced by another American, Leo Pruneau, a graduate of the ArtCenter College of Design in Los Angeles, who headed up the studio until 1983.

The following year, after almost 20 years of American direction, the baton was handed over to Melbourne-born Phillip Zmood. He was followed, in turn, by Australians Michael Simcoe (1998–2004), Anthony Stolfo (2004–12), Andrew Smith (2012–13) and Richard Ferlazzo (2013–20). While Ferlazzo oversaw the closing of GMH Design in 2020, GMH’s legacy continues to influence the GM global corporation: Andrew Smith is the executive director of Global Cadillac and Buick Design, and Michael Simcoe was appointed the vice president of GM Global Design in 2016, occupying Harley Earl’s office.

As Smith has noted: ‘One reason I believe Australians have been quite successful at GM in the US is because we had the opportunity to work at a smaller version of the same organization. We were able to learn our trade at GMH and then apply it in the US.’ Zmood also thought that the small size (relative to Detroit) of the GMH operation forced its designers to be agile:

Holden Design benefited to some degree by being smaller in number and the designers had to come up with design themes quickly and then participate in the model making guidance, technical/engineering solutions etc.

This approach meant that the team bonded and needed to realise the releasing of the design/body surface as quickly as possible. The design team became very efficient as they often had go outside their comfort zone to achieve their design in the Australian situation, low volume and limited funds.

The following year, after almost 20 years of American direction, the baton was handed over to Melbourne-born Phillip Zmood. He was followed, in turn, by Australians Michael Simcoe (1998–2004), Anthony Stolfo (2004–12), Andrew Smith (2012–13) and Richard Ferlazzo (2013–20). While Ferlazzo oversaw the closing of GMH Design in 2020, GMH’s legacy continues to influence the GM global corporation: Andrew Smith is the executive director of Global Cadillac and Buick Design, and Michael Simcoe was appointed the vice president of GM Global Design in 2016, occupying Harley Earl’s office.

As Smith has noted: ‘One reason I believe Australians have been quite successful at GM in the US is because we had the opportunity to work at a smaller version of the same organization. We were able to learn our trade at GMH and then apply it in the US.’ Zmood also thought that the small size (relative to Detroit) of the GMH operation forced its designers to be agile:

Holden Design benefited to some degree by being smaller in number and the designers had to come up with design themes quickly and then participate in the model making guidance, technical/engineering solutions etc.

This approach meant that the team bonded and needed to realise the releasing of the design/body surface as quickly as possible. The design team became very efficient as they often had go outside their comfort zone to achieve their design in the Australian situation, low volume and limited funds.

A community of practice

The designers represented in this exhibition span the 56-year history of the Technical Centre, from Peter Nankervis, who was there at the beginning in 1964, to Richard Ferlazzo, who oversaw its closure in 2020. What became apparent during conversations with them was that they had created in the studio a powerful collaborative culture of which they were, and are still, extremely proud. It was this idea of the collaborative studio, and the building of a ‘community of practice’ both within the Technical Centre and the overseas GM studios, that became the focus and theme for the exhibition. Andrew Smith, for example, reflected:

I have also always approached car design as a team sport. I never felt I was the best at rendering but I really enjoyed being part of the team and working the details. The studio I was introduced to as a young designer was a truly phenomenally talented team.

Viewed in this light, we can align their work to other design studio models more familiar to design historians and practitioners, such as the graphic design studio, fashion studio or even the architecture studio. As Dhaval Vyas, Gerrit van der Veer and Anton Nijholt note in their examination of design studio culture, ‘The role of collaboration between co-designers is critical to a design studio’s creativity’. They elaborate:

A typical design studio, professional or academic, has a high material character – in the sense that it is full of material objects and design artefacts; office walls and other working surfaces full of post-it notes, sketches and magazine clips for sharing ideas and inspiration; physical models and prototypes lying on the desk and so on.

This comment goes to the heart of how we might describe the design studio at the GMH Technical Centre. As Richard Ferlazzo has noted, ‘the motor car is the most complex consumer product on the market so it presents many design and engineering challenges. It is the ultimate expression of art & science, combining style and quality with technology and dynamics’.19 The production of such a complex object has produced, over the last century, particular industrial processes and ways of working which generate their own culture:

The atmosphere in a Design Studio is always highly charged; it is both competitive and collaborative. The design process begins with complete freedom of individual expression and exploration. Through collective interaction of the experienced group, ideas are refined and improved through an iterative process. Ultimately, a single direction is chosen and the work dynamic changes from ‘competitive’ to ‘collaborative’ as the team assumes shared ownership of developing the optimal outcome.

A successful studio will have a culture of open sharing of ideas, encouragement and support for other team members and the willingness to impart knowledge and experience.

Like Ferlazzo, Smith recalled that automotive design was a ‘team sport’:

The studios were very much a collective. The balance of competition and collaboration was just about perfect … When I started at Holden, Phil Zmood was director, Peter was chief designer for the joint venture studios (Studio 6), Mike Simcoe was chief designer for the main studios, Richard Ferlazzo was assistant chief. Peter Hughes, John Field and I sat in Studio 2. It was a great work environment, lots of creativity and lots of idle banter about music on the radio, the next big concept car from Europe, the latest trends in Japan … We used to also critique each other’s work. John … was incredibly talented and an out of the box thinker. Pete was naturally gifted and could translate an idea from sketch to clay with ease.

This ethos of collaborative design was echoed by John Schinella, who, from the vantage point of 2021, recalled his years in Melbourne with Schemansky as ‘an amazing time to be at Holdens and working with and being part of a great creative group of people at that time in history’

The designers represented in this exhibition span the 56-year history of the Technical Centre, from Peter Nankervis, who was there at the beginning in 1964, to Richard Ferlazzo, who oversaw its closure in 2020. What became apparent during conversations with them was that they had created in the studio a powerful collaborative culture of which they were, and are still, extremely proud. It was this idea of the collaborative studio, and the building of a ‘community of practice’ both within the Technical Centre and the overseas GM studios, that became the focus and theme for the exhibition. Andrew Smith, for example, reflected:

I have also always approached car design as a team sport. I never felt I was the best at rendering but I really enjoyed being part of the team and working the details. The studio I was introduced to as a young designer was a truly phenomenally talented team.

Viewed in this light, we can align their work to other design studio models more familiar to design historians and practitioners, such as the graphic design studio, fashion studio or even the architecture studio. As Dhaval Vyas, Gerrit van der Veer and Anton Nijholt note in their examination of design studio culture, ‘The role of collaboration between co-designers is critical to a design studio’s creativity’. They elaborate:

A typical design studio, professional or academic, has a high material character – in the sense that it is full of material objects and design artefacts; office walls and other working surfaces full of post-it notes, sketches and magazine clips for sharing ideas and inspiration; physical models and prototypes lying on the desk and so on.

This comment goes to the heart of how we might describe the design studio at the GMH Technical Centre. As Richard Ferlazzo has noted, ‘the motor car is the most complex consumer product on the market so it presents many design and engineering challenges. It is the ultimate expression of art & science, combining style and quality with technology and dynamics’.19 The production of such a complex object has produced, over the last century, particular industrial processes and ways of working which generate their own culture:

The atmosphere in a Design Studio is always highly charged; it is both competitive and collaborative. The design process begins with complete freedom of individual expression and exploration. Through collective interaction of the experienced group, ideas are refined and improved through an iterative process. Ultimately, a single direction is chosen and the work dynamic changes from ‘competitive’ to ‘collaborative’ as the team assumes shared ownership of developing the optimal outcome.

A successful studio will have a culture of open sharing of ideas, encouragement and support for other team members and the willingness to impart knowledge and experience.

Like Ferlazzo, Smith recalled that automotive design was a ‘team sport’:

The studios were very much a collective. The balance of competition and collaboration was just about perfect … When I started at Holden, Phil Zmood was director, Peter was chief designer for the joint venture studios (Studio 6), Mike Simcoe was chief designer for the main studios, Richard Ferlazzo was assistant chief. Peter Hughes, John Field and I sat in Studio 2. It was a great work environment, lots of creativity and lots of idle banter about music on the radio, the next big concept car from Europe, the latest trends in Japan … We used to also critique each other’s work. John … was incredibly talented and an out of the box thinker. Pete was naturally gifted and could translate an idea from sketch to clay with ease.

This ethos of collaborative design was echoed by John Schinella, who, from the vantage point of 2021, recalled his years in Melbourne with Schemansky as ‘an amazing time to be at Holdens and working with and being part of a great creative group of people at that time in history’

Ways of working

Vyas, van der Veer and Nijholt note: The type of information that is communicated between designers is multimodal, multisensory, ubiquitous and touches the artistic, emotional and experiential side of the designers’ thinking, in addition to their instrumental and practical reasoning.

Within this collective community of practice, each designer at GMH developed their specialism and way of working. They came to the studio from different training and experiences. In the early years, some were recruited from technical high schools and some were more or less self-taught and were trained at GMH.

But as industrial design programs developed at Australian technical universities, such as RMIT, Swinburne and University of Technology Sydney, recruits to GMH Design had a sound design foundation; once in the design studio their skills were honed, shared and developed. Initially, says John Field, ‘[I] looked to sketches in magazines by designers such as Mark Stehrenberger and David Bentley. This led to a precise, technical style using sweeps and templates, but once in the industry I also needed to develop a faster, more freehand style’.

Andrew Smith ‘originally intended to study architecture and always liked a very technical style. I remember there was a Japanese publication, Magazine X, that used to have an illustrator of future vehicles who had a style I always admired. Almost a mix of architectural drawings and water color …. Skills were handed down and across the industry, as Smith notes:

As designers we were influenced and trained by the more experienced staff, and occasionally designers from the US or Europe would spend time in the studios and pass on their knowledge. Specialist automotive design magazines were also a source of inspiration for new techniques. However we also learnt from our peers and strove to leapfrog each other in the spirit of friendly competiveness. I do recall it getting a bit out of hand and doing sketches with aircraft in the background that had more attention paid to them than the cars, and Phil Zmood telling me to rein it in.

Peter Nankervis recalls that ‘often viewing others work and techniques provides inspiration which influences your style’, and yet he in turn was for Smith ‘a great mentor’, who ‘would tell us to tape and retape lines, moving them mm’s but ultimately making the drawing truly sing’.28 The mobility of Australian designers was also an advantage, as Zmood notes:

Australian automotive designers and support staff are probably the most travelled overseas work group, our opportunity to travel and work overseas resulted in fresh and creative solutions with a twist of Australian culture which has had significant design impact within Australia and internationally.

Step inside Mike Simoe's office

VE News - Ten minutes with Tony Stolfo

Mike Simcoe on his journey to from Melbourne to Motown

Richard Ferlazzo’s one-of-a-kind vehicle honours generations of classic models

Joe Schemansky led the styling of some of Australia’s best loved and most iconic cars

Note: The Exhibition was at the City Gallery, Melbourne Town Hall during 2021.

Source: Permission from Harriet Edquist, Emeritus Professor of RMIT's School of Architecture and Urbam Design to refer to their content and photos.

Vyas, van der Veer and Nijholt note: The type of information that is communicated between designers is multimodal, multisensory, ubiquitous and touches the artistic, emotional and experiential side of the designers’ thinking, in addition to their instrumental and practical reasoning.

Within this collective community of practice, each designer at GMH developed their specialism and way of working. They came to the studio from different training and experiences. In the early years, some were recruited from technical high schools and some were more or less self-taught and were trained at GMH.

But as industrial design programs developed at Australian technical universities, such as RMIT, Swinburne and University of Technology Sydney, recruits to GMH Design had a sound design foundation; once in the design studio their skills were honed, shared and developed. Initially, says John Field, ‘[I] looked to sketches in magazines by designers such as Mark Stehrenberger and David Bentley. This led to a precise, technical style using sweeps and templates, but once in the industry I also needed to develop a faster, more freehand style’.

Andrew Smith ‘originally intended to study architecture and always liked a very technical style. I remember there was a Japanese publication, Magazine X, that used to have an illustrator of future vehicles who had a style I always admired. Almost a mix of architectural drawings and water color …. Skills were handed down and across the industry, as Smith notes:

As designers we were influenced and trained by the more experienced staff, and occasionally designers from the US or Europe would spend time in the studios and pass on their knowledge. Specialist automotive design magazines were also a source of inspiration for new techniques. However we also learnt from our peers and strove to leapfrog each other in the spirit of friendly competiveness. I do recall it getting a bit out of hand and doing sketches with aircraft in the background that had more attention paid to them than the cars, and Phil Zmood telling me to rein it in.

Peter Nankervis recalls that ‘often viewing others work and techniques provides inspiration which influences your style’, and yet he in turn was for Smith ‘a great mentor’, who ‘would tell us to tape and retape lines, moving them mm’s but ultimately making the drawing truly sing’.28 The mobility of Australian designers was also an advantage, as Zmood notes:

Australian automotive designers and support staff are probably the most travelled overseas work group, our opportunity to travel and work overseas resulted in fresh and creative solutions with a twist of Australian culture which has had significant design impact within Australia and internationally.

Step inside Mike Simoe's office

VE News - Ten minutes with Tony Stolfo

Mike Simcoe on his journey to from Melbourne to Motown

Richard Ferlazzo’s one-of-a-kind vehicle honours generations of classic models

Joe Schemansky led the styling of some of Australia’s best loved and most iconic cars

Note: The Exhibition was at the City Gallery, Melbourne Town Hall during 2021.

Source: Permission from Harriet Edquist, Emeritus Professor of RMIT's School of Architecture and Urbam Design to refer to their content and photos.

Copyright 2023 Cartalk Australia